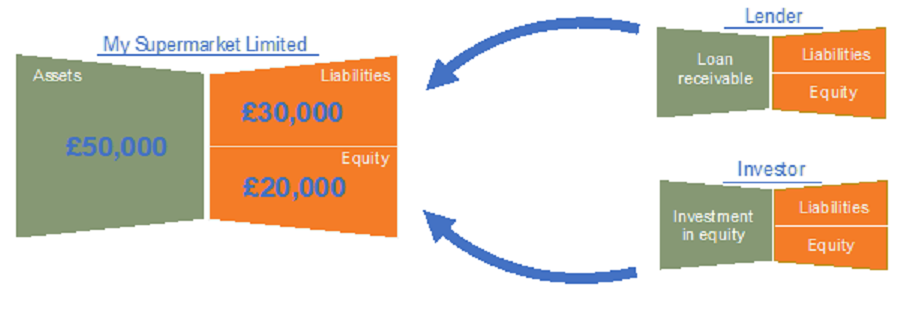

A good question to ask at this point is “what’s the value of this enterprise?”. The answer, of course, depends on point of view.

You might be inclined to say that the business is worth £20,000 and this is true, but only from the point of view of investors. The valuable thing is actually ”investment in equity”—an asset in the investor’s butterfly.

Ambiguity over point of view is common throughout accounting education, but especially so when explaining the nature of equity, even among the accounting profession and its regulators. It’s also a cause of much confusion among students.

What about from the lender’s point of view? The value of the entity is the loan of £30,000, which is an asset in the lender’s butterfly.

The enterprise value, if defined as equity and debt finance, is £50,000.

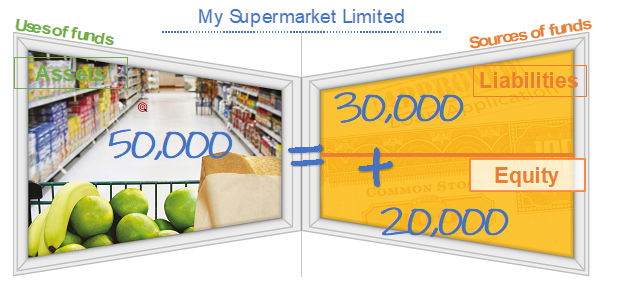

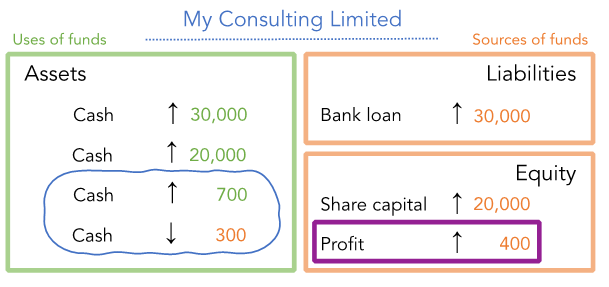

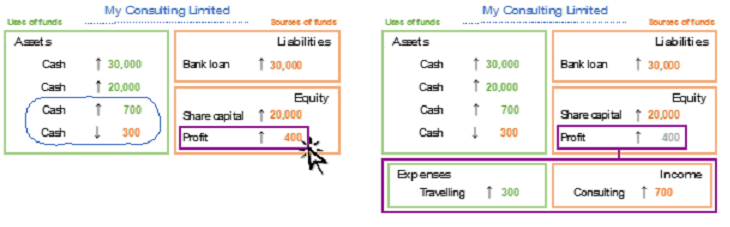

From the entity’s point of view, the purest answer is to say that the entity is worth nothing. The value of assets is equal to the sources of funding for those assets, which gives us the accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

So, depending on perspective, it can be argued that the entity value presented on the balance sheet is nil, £20,000, £30,000 or £50,000. This is not evasive or misleading, but a self-evident truth that reflects the purpose and nature of accounting.